Mortal Limits

Biomedical ethicist Daniel Callahan wrote that, in our parent’s time, persons used to die of natural causes, but today we no longer have that luxury. Callahan was writing about the frenzied exercise of medicine to keep terminally ill patients alive, at great expense to survivors and soci ety. Commonly, family members and medical teams collude in the work of preventing death at all costs. Callahan commented that, in the medical culture shared by both doctors and patients, “natural causes” of death no longer exist; every death is treated as a preventable failure on the part of medicine.

The truth is, of course, that the body dies. Before death, gravity takes its toll on organs and tissues. What was taut and firm now points south. With aging, bodies get smaller, saggier, and weaker. For many, if not most persons, these hints of mortality are an insult. In response, Western culture is replete with strategies to counter this insult: elective plastic surgery, fat farms, and December-June marriages. The culture of youth is as vibrant as its television advertisements. The limits of mortality are denied. Against this denial of mortal limits, sex is a sign of life. And so it should be. It requires, as has been said repeatedly here, a minimum level of physiological health. In its procreative expression, sex promises future lives if not future life. But sex can also be used as a device to deny limits that, to borrow Callahan’s phrase, are “natural causes.” The loss or decline of sexual function is a hint of mortality. There is a distinct value judgment to be made about how attentive one should be to hints of mortality. If one takes the position, as I do, that hints of mortality are part and parcel of life that should be listened to, then one should listen to and accept the limits of sexual function without ceaseless somatic interventions. Employing somatic treatments over and over again to deny eventual mortality does little to enrich the sexual life of a couple. Indeed, it may do much to distract from an appreciation of their total life together during the time remaining to them.

The tragedy of September 11, 2001, gave rise to a cultural appreciation of the limits and fragility of life. Persons about to die called their dear ones on cell phones to express their love in their final minutes. Those of us who were survivors, like survivors everywhere, generally expressed in our grief a greater appreciation of “the important things of life” and an intention to “take time to do the really important things.” What made this possible was the terrible shout of mortality rising from the crashes of September 11. We heard our mortality and returned to our lives to live them more intentionally.

On a personal level, the many hints of mortality that an individual or couple receives can, and I suggest should, be used for the same purpose of living more intentionally. While somatic treatments for sexual dysfunction may be part of that living intentionally, they may also be part of a collusion to deny mortality at all costs.

SUMMARY

The disease perspective takes the somatic reality of sex seriously. It states that sex is, at its bedrock, a corporal event. To the extent that disease, injury, surgery, medication, and drugs compromise the physiological functioning of the body, to that same extent sexual functioning may be compromised. The clinician working to understand a sexual problem from the disease perspective evaluates the patient’s physical and psychological history as well as his or her family medical and psychological history. Although there may be many psychosocial factors that should be noted and treated in due course, the clinician employing the disease perspective wants to be sure that the body is working as well as it can. If somatic treatments will improve sexual functioning, the clinician informs the patient about them and assists in their integration. When the body signals that it has reached its highest level of sexual functioning given its limitations of disease or aging, the clinician understands that signal and turns to another perspective, the life story perspective, to assist the patient in heeding the meaning involved.

Disease

Diabetes and normal aging (menopause) are two real somatic conditions that affected Mark and Esther’s ability to function sexually. As such, the diabetes and postmenopausal conditions deserve to be the object of somatic treatment. Perhaps other, psychological interpretations might have been developed to understand their sexual problems. Mark might have been passive aggressive in not treating his erectile dysfunction sooner. Esther, as a consequence of her sense of rejection, might have refused hormone replacement treatment as a way of withholding herself as a potential sexual partner. And there certainly may have been numerous nonsexual marital tensions or differences that could serve as the focus of lengthy marital therapy. But Mark had diabetes and Esther had atrophic vaginal walls.

The disease perspective says that the clinician should first examine all the somatic conditions and diseases that might play a causal role before rushing on to a more psychological understanding of the sexual dysfunction. For the physician, this is professionally instinctive; for the nonphysician with a treatment quiver filled with psychological approaches and interpretations, ruling out diseases and somatic conditions is usually a skill deliberately learned. Nonphysician mental health providers must develop a level of knowledge about the diseases affecting sexual function that is superior to that of the educated layperson. They must also have a good working relationship with primary care physicians, urologists, and gynecologists, both for their own continuing education and for mutual patient referrals.

The Past Is Prologue

In the somatic treatment of sexual dysfunction, it is important to observe the limits posed by premorbid sexual function. “Past is prologue” in the sense that the baseline level of sexual function for the years preceding the onset of the disease is probably going to be the optimum level of functioning possible with the most successful of somatic treatments. A common medical phrase is “return to baseline”: the patient returns to the level of function (e.g., cardiac, pulmonary) that he or she had before a disease or critical event.

Mark and Esther will in all probability never have more interest in sex or more frequent sex than they did before the onset of Mark’s diabetes. While the “finding again” of each other sexually will undoubtedly enrich their marriage, after their second honeymoon their sexual life will probably settle into the baseline value they placed on sex twelve years ago. This is realistic, not pessimistic. It is a realism that is aided by the disease perspective, with its sensitivity to somatic limits posed by illnesses and injuries even though much of the baseline of sexual life is determined by factors other than somatic.

These nonsomatic factors make the return to baseline not merely a realistic compromise between ideals and reality but also a goal to strive for. After many decades, aging bodies and the ebbing of all novelty demand that the physiological drive for sex be supplemented by motivations of caring, sensuality, and need for intimacy. Helping couples to recall their baseline level of sexual life gives them a joint goal to aim for. Memory and imagination can be employed to picture the type of sexual life the future may hold for them. The clinician’s role is—to use the saying usually applied to parents—to give their patients both ground and wings: the ground of accepting the limitations imposed by somatic conditions; the wings of imagining new meanings and ways of coming together sexually.

The most remarkable change in the treatment of sexual disorders in the past two decades has been the emergence of somatic treatments. In ear lier years, the only somatic interventions had been surgeries and topical applications. The surgeries included procedures such as insertion of a penile prosthesis and reconstruction of vulvar and vaginal tissue. Topical aids were vaginal lubricants and attempts, usually unsuccessful, to apply an anesthetic to the penis to retard premature ejaculation. In the past twenty years, however, the primary somatic treatment of male sexual dysfunction has been the use of oral medications such as Viagra, intracavernosal injections, and penile vacuum devices. The goal of the treatment is, obviously, to produce an erection capable of penetration. It is an organ- specific goal; there is no claim that the presence of an erection will make the man want to use it sexually—let alone that his partner will want to.

For women, the goal of somatic treatment is likewise directed toward improving the genital environment so that it can contain the penis and respond with pleasurable sensations rather than pain. Vaginal lubricants are sold over the counter and are widely used successfully. For women with hormone deficiencies due to surgery or for postmenopausal women, estradiol vaginal tablets improve lubrication and make the vaginal epithelium thicker. Exogenous androgen is also employed for androgen-deficient women (e.g., those who have had their ovaries removed) to increase sexual desire, but this remains a controversial treatment. A product called EROS-CTD serves as a suction device on the clitoris, improving clitoral engorgement and presumably the potential for vaginal lubrication, subjective arousal, and orgasm. At present, research is being conducted on vasoactive medications for sexual arousal in women, comparable to the Viagra-assisted arousal in men.

A full review of the somatic treatments of sexual dysfunctions and disorders is not the purpose here and is available elsewhere. Instead, I offer some comments on somatic treatments from the disease perspective in the context of a typical case.

■ Mark and Esther had been married for thirty-nine years. During the last ten years they had not had intercourse, because of Mark’s erectile dysfunction brought on by diabetes. The diabetes was well controlled in recent years, and Mark had felt guilty about not being able to have intercourse with Esther. In preparation for their fortieth wedding anniversary, Mark obtained a prescription for Viagra from his primary care doctor. He tested it privately and, with some manual simulation, obtained a full erection such as he had not experienced in years. He could not wait for their anniversary to surprise Esther. As might have been predicted by even a casual observer, the anniversary bedroom scene was not a happy one. Having taken the Viagra an hour before retiring, and with some minimal self-stimulation, Mark had a full erection. Esther had reconciled herself years ago to a marriage that was sensual but not sexual. She had not taken hormone replacement after menopause, because she had some medical concerns and, in any case, they weren’t having intercourse. Now here they were: forty years of marriage, ten years without intercourse, Mark with a full erection—and Esther with no psychological or physiological preparation for intercourse. Following some conversation, during which Mark lost the erection, they decided to try intercourse. After some time and stimulation, Mark was able to get an erection. It was difficult to penetrate Esther, and when he finally did it was quite painful for her. He withdrew immediately, with orgasm for neither. It was about two months before they felt able to seek help, so hurt and embarrassed were they about the failure of communication and the physical pain Mark had caused Esther. The work of the sexual therapy was to assist them to gradually integrate the use of Viagra into their sexual life. It necessitated a switch of focus from his penis to her arousal, both emotional and in terms of vaginal lubrication. After discussing the pros and cons with her internist, Esther began hormone replacement therapy, which made her “generally feel better.” Gradually, over a period of four months, the couple progressed in sensate focus therapy, from sensual rapprochement to sexual engagement to successful intercourse about every three weeks.

Integration

The somatic treatments, as briefly described above, offer women and men an opportunity to restore sexual function in situations where disease, surgery, aging, or even psychological factors have made it impossible. These treatments are widely prescribed by primary care physicians and by specialty physicians such as urologists and gynecologists, and many of the somatic treatments are available over the counter. Millions of people will try them; the challenge is whether or not the somatic treatments will be integrated into the sexual lives of those who use them. The case of Mark and Esther is patently a situation of non-integration in the introduction of Mark’s use of Viagra. Mark’s attention was too selffocused on the presence of an erection. He forgot that coming together sexually, for two people who care for and are committed to each other, entails more than an erect penis. He was probably totally ignorant of the possible condition of his wife’s postmenopausal vagina in the absence of hormone replacement.

Integration of somatic treatments of sexual dysfunction recognizes that the treatments are directed to the genital organs. Their effect is to make the genitals capable of responding sexually. The work of integration is to harmonize improvements in physiological functioning of the genitals with an emotional desire and readiness for the sexual activity. This integration does not require professional assistance for most couples— most can incorporate the somatic treatments into their sexual life through open communication with each other. But other couples, such as Mark and Esther, find themselves unable to use the somatic advances without professional assistance in the work of integration. The art of sexual therapy with such a couple is to provide assistance while being as unobtrusive and noninvasive of their sexual and intimate life as possible. Sexual therapy entails assisting couples to do the work of emotional, sensual, and sexual integration.

The disease perspective makes sense ultimately when considered against a background of healthy function. Disease is an aberration of healthy cells or physiological functioning. Therefore, the disease perspective on problems of sex must also consider issues relating to the healthy body and sex.

From the viewpoint of physical health alone, sexual activity is exercise and as such is good for the general health of the body. Circulation is increased, muscles stretched, and endorphins released. But as with any exercise, the question may become one of quantity. In other words, is too much sex harmful to the body?

For men, there is a refractory period after ejaculation when a subsequent ejaculation is not possible. The refractory period gradually increases with aging, from minutes in a young man to several hours in an older man. This serves as a natural limit-setting mechanism. For women, dyspareunia—pain with intercourse—is a marker that the vaginal tissue is not prepared for more penetrative activity. The friction of the penis is not assuaged by vaginal lubrication and so pain occurs. Pain may also occur in women and men who manually stimulate their genitals to excess. Pain from abrasions, usually around the glans penis or clitoris, suggests that the skin of the glans is being damaged by too much sexual activity. But apart from the helpful signals of pain—in sexual organs or in other parts of the body (e.g., chest pain)—the effects of sexual activity on a healthy body are comparable to other forms of physical activity: sexual activity is good for the general health of the body.

From the viewpoint of psychological health and social adjustment, the question of too much sexual activity is usually relevant and, to be candid, controversial. Our culture is not one that likes limits—especially sexual limits or limits on what one can do with one’s body. From abortion to use of protective headgear for cyclists, any attempt to suggest, let alone legislate, limits on individual choice will be met with heated opposition.

Nevertheless, there is a point at which sexual activity can be detrimental to psychological health and social adjustment. The parallel with exercise is again helpful here. The norm to be used in addressing the question of whether a level of sexual activity is too much is whether the activity interferes with one’s psychological maturation or occupational or social functioning. Hours and hours spent in the gymnasium or in a sporting activity daily must detract from the development of other intellectual and interpersonal skills and relationships. Hours and hours thinking about, pursuing, and/or consummating sexual activity must also detract from the development of other intellectual and interpersonal skills and relationships. In this situation, then, too much sex (including thinking about sex) is not healthy for the whole person. I will have more to say about this when discussing the “overvalued idea” in the behavior perspective.

Can too little sexual activity hurt the body? There is no evidence that too little or no sexual activity does physical harm to the body. We know that during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, individuals have a sexual response in terms of vaginal lubrication and erection. It is hypothesized that one of the functions of the lubrication and erection during sleep is oxygenation of the tissues involved. Nighttime sexual arousal may act as a preservative of the tissues necessary for sexual health. In the same self-regulatory manner, nocturnal emissions and ejaculations in men maintain a comfortable level of seminal fluid.

It is common wisdom that most physical activities have a “use it or lose it” factor. Muscles should be stretched; psychological resistance to physical inertia should be routinely surmounted. The same wisdom applies to sexual activity. Especially for postmenopausal women, the normal stretching of vaginal tissues during intercourse serves to preserve suppleness in the vaginal walls. For both men and women, sexual activity usually involves more than the genitals. Torso and limbs move, breathing increases, and the body is exercised. From a physical viewpoint alone, the “use it or lose it” wisdom does have application to sexual activity. Studies of the sexual activity of older persons repeatedly report that the greatest predictor of the level of sexual activity in older age is the amount of sexual activity during the individual’s younger years.

Most physicians suggest that treatments for impotence proceed along a path moving from least invasive to most invasive. This means cutting back on any harmful drugs is considered first. Psychotherapy and behavior modifications are considered next, followed by vacuum devices, oral drugs, locally injected drugs, and surgically implanted devices (and, in rare cases, surgery involving veins or arteries).

Psychotherapy

Experts often treat psychologically based impotence using techniques that decrease anxiety associated with intercourse. The patient’s partner can help apply the techniques, which include gradual development of intimacy and stimulation. Such techniques also can help relieve anxiety when physical impotence is being treated.

Drug Therapy

Drugs for treating impotence can be taken orally, injected directly into the penis, or inserted into the urethra at the tip of the penis. In March 1998, the Food and Drug Administration approved sildenafil citrate (marketed as Viagra), the first oral pill to treat impotence. Taken 1 hour before sexual activity, sildenafil works by enhancing the effects of nitric oxide, a chemical that relaxes smooth muscles in the penis during sexual stimulation, allowing increased blood flow. While sildenafil improves the response to sexual stimulation, it does not trigger an automatic erection as injection drugs do. The recommended dose is 50 mg, and the physician may adjust this dose to 100 mg or 25 mg, depending on the needs of the patient. The drug should not be used more than once a day.

Oral testosterone can reduce impotence in some men with low levels of natural testosterone. Patients also have claimed effectiveness of other oral drugs–including yohimbine hydrochloride, dopamine and serotonin agonists, and trazodone–but no scientific studies have proved the effectiveness of these drugs in relieving impotence. Some observed improvements following their use may be examples of the placebo effect, that is, a change that results simply from the patient’s believing that an improvement will occur.

Many men gain potency by injecting drugs into the penis, causing it to become engorged with blood. Drugs such as papaverine hydrochloride, phentolamine, and alprostadil (marked as Caverject) widen blood vessels.

These drugs may create unwanted side effects, however, including persistent erection (known as priapism) and scarring. Nitroglycerin, a muscle relaxant, sometimes can enhance erection when rubbed on the surface of the penis.

A system for inserting a pellet of alprostadil into the urethra is marketed as MUSE. The system uses a pre-filled applicator to deliver the pellet about an inch deep into the urethra at the tip of the penis. An erection will begin within 8 to 10 minutes and may last 30 to 60 minutes.

The most common side effects of the preparation are:

- aching in the penis, testicles, and area between the penis and rectum;

- warmth or burning sensation in the urethra;

- redness of the penis due to increased blood flow;

- minor urethral bleeding or spotting.

Research on drugs for treating impotence is expanding rapidly. Patients should ask their doctors about the latest advances.

Vacuum Devices

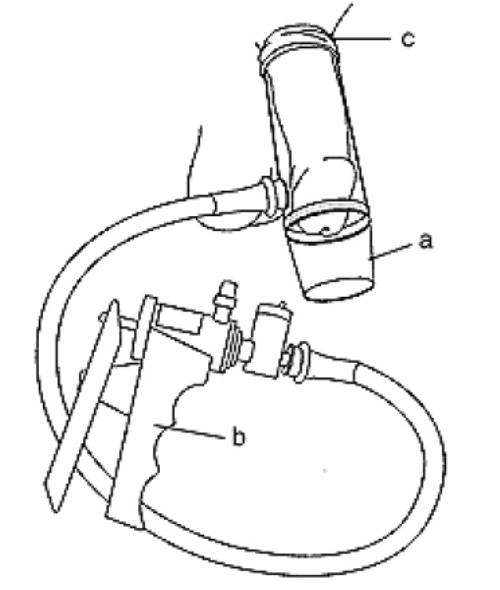

Mechanical vacuum devices cause erection by creating a partial vacuum around the penis, which draws blood into the penis, engorging it and expanding it. The devices have three components: a plastic cylinder, in which the penis is placed; a pump, which draws air out of the cylinder; and an elastic band, which is placed around the base of the penis, to maintain the erection after the cylinder is removed and during intercourse by preventing blood from flowing back into the body (see figure).

One variation of the vacuum device involves a semirigid rubber sheath that is placed on the penis and remains there after attaining erection and during intercourse.

Surgery

Surgery usually has one of three goals:

- To implant a device that can cause the penis to become erect,

- To reconstruct arteries to increase flow of blood to the penis,

- To block off veins that allow blood to leak from the penile tissues.

Implanted devices, known as prostheses, can restore erection in many men with impotence. Possible problems with implants include mechanical breakdown and infection. Mechanical problems have diminished in recent years because of technological advances.

Malleable implants usually consist of paired rods, which are inserted surgically into the corpora cavernosa, the twin chambers running the length of the penis. The user manually adjusts the position of the penis and, therefore, the rods. Adjustment does not affect the width or length of the penis.

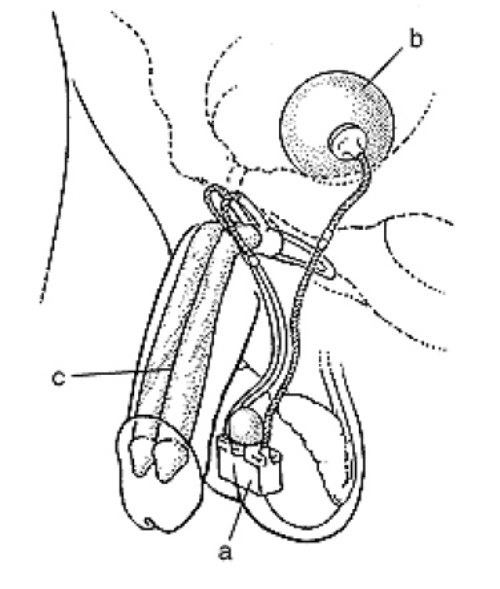

Inflatable implants consist of paired cylinders, which are surgically inserted inside the penis and can be expanded using pressurized fluid (see figure). Tubes connect the cylinders to a fluid reservoir and pump, which also are surgically implanted. The patient inflates the cylinders by pressing on the small pump, located under the skin in the scrotum. Inflatable implants can expand the length and width of the penis somewhat. They also leave the penis in a more natural state when not inflated.

With an inliatable implant, erection Is produced by squeezing a small pump (a) implanted in the scrotum. The pump causes fluid to flow Irom a reservoir (b) residing in Ihe lower pelvis to two cylinders (c) residing in the penis. The cylinders expand to create ihe erection.

Surgery to repair arteries can reduce impotence caused by obstructions that block the flow of blood to the penis. The best candidates for such surgery are young men with discrete blockage of an artery because of an injury to the crotch area or fracture of the pelvis. The procedure is less successful in older men with widespread blockage.

Surgery to veins that allow blood to leave the penis usually involves an opposite procedure–intentional blockage. Blocking off veins (ligation) can reduce the leakage of blood that diminishes rigidity of the penis during erection. However, experts have raised questions about this procedure’s long-term effectiveness.

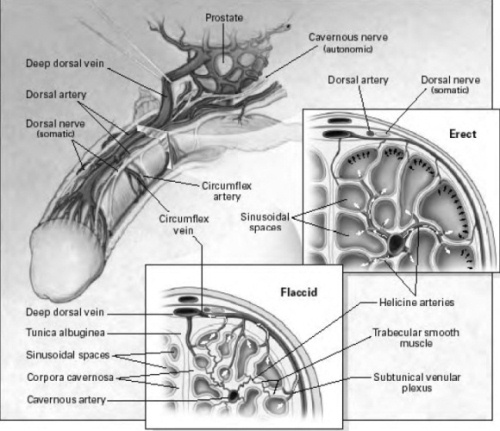

A normal erection requires the penis’ nerves and blood vessel systems to be intact and to have appropriate hormonal levels, but also is moderated by psychological factors. The penis is stimulated by both the autonomic nervous system — the part of the nervous system that functions independent of our conscious thought — and the somatic nervous system — the nervous system responsible for sensation and contraction of muscles attached to the penis. The glans or head and body of the penis have numerous sensory nerve endings that send messages of pain, temperature and touch back to the brain. The motor nerves stimulate the muscles in the pelvis and penis — the ischiocavernosus and bubocavernosus muscles — that are necessary to produce a rigid erection and ejaculation. The autonomic nervous system stimulates the rectum, bladder, prostate and sphincters, includes the cavernous nerve that stimulates the penis and controls the flow of blood during and after erection.

With sexual stimulation, the cavernous nerves release chemicals that significantly increase blood flow to the penis. The erectile tissue of the penis rapidly fills, expands and becomes erect. During sexual activity, the bulbocavernous and ischiocavernous muscles of the penis are stimulated, which compresses the base of the penis to make the penis even harder.

During emission, seminal fluid is released from the seminal vesicles and the prostate into the urethra. The bladder sphincter then closes, and the seminal fluid becomes trapped. As the amount of fluid builds in the urethra, the pressure increases and the sensation of the inevitability of ejaculation is experienced. The bulbocavernous muscle contracts and expels the semen forcibly from the urethra. Orgasm normally coincides with ejaculation.

Detumescence, or loss of erection, occurs shortly thereafter and is produced by the breakdown of the factors that cause erection.

Anatomy and Mechanism of Penile Erection

The cavernous nerves travel from the underside of the penis to the prostate. These nerves regulate blood flow within the penis during erection and flaccidity. In the flaccid state, inflow through the arteries is minimal and there is free outflow via the small veins exiting the spongy tissue just under the thick tunica (thick membrane surrounding the spongy tissue). During erection, the smooth muscle in the penis relaxes while the arteries widen to pump in more blood that expands the three cavities of the penis — also called sinusoidal spaces — to lengthen and enlarge the penis. The expansion of these cylinders compresses the small veins and reduces the outflow of blood.

Future Directions

Innovative research over the past several years has resulted in significant strides and improvement to understanding the anatomy and physiology of sexual function. For instance, increasing knowledge about details of the cavernous nerves in the pelvis led to refinement of nerve-sparing prostatectomy. Understanding the biochemistry of normal sexual functioning led to the development of medications including Sildenafil, Cialis and Levitra.

Current research is focusing on further understanding of the specific physiologic pathways responsible for normal sexual function, developing new, more effective agents for managing impotence and understanding how cavernous nerves heal and what factors can hasten the healing process. Use of “gene” or “stem cell” technology may be possible in the future, allowing men and their partners to enjoy better sexual health.

In patients who only have partial erections or who either do not respond to other treatments or prefer not to use them, a vacuum device maybe useful. The device consists of a plastic cylinder connected to a pump and a constriction ring. A vacuum pump uses either manual or battery power to create suction around the penis and bring blood into it; a constriction device is then released around the base of the penis to keep blood in the penis and maintain the erection. A vacuum device can be used safely for up to 30 minutes, which is when the constriction device should be removed. The advantage of such a device is it is relatively inexpensive, easy to use and avoids drug interactions and side effects. Side effects may include temporary penile numbness, trapping the ejaculate and some bruising.

Penile prosthesis

For men with erectile dysfunction who have failed or cannot tolerate other treatments, a penile prosthesis offers an effective, but more invasive alternative. Prostheses come in either a semi-rigid form or as an inflatable device. Most men prefer the placement of the inflatable penile prosthesis.

The placement of the prosthesis within the penis requires the use of an anesthetic. A skin incision is made either at the junction of the penis and scrotum, or just above the penis, depending on which prosthesis and technique is used. The spongy tissue of the penis is exposed and dilated; the prosthesis is then sized and the proper device is then placed. The inflatable device — a pump that contains the inflation and deflation mechanism — is placed in the scrotum. The patient can control his erection at will by pushing a button under the skin. Although placement of the prosthesis requires a surgical procedure, patient and partner satisfaction rates are as high as 85 percent. Full penile length might not be restored to the patient’s natural erect status. Rare side effects include infection, pain and device malfunction or failure. As the nerves that control sensation are not injured, the penile sensation and the ability to have an orgasm should be maintained.

Psychological Causes of Impotence

Common causes of psychogenic impotence include depression and performance anxiety. Depression is associated with decreased energy, interest and decreased libido or desire. Performance anxiety, work stress or strained personal relationships can affect erectile function in both conscious and subconscious ways.

Neurogenic Impotence

Penile erection depends on an intact nervous system so any injury to the nervous system involved in erections may cause impotence. Diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke or head injury can lead to impotence by affecting the libido, or by preventing the initiation of the nerve impulses responsible for erections. Patients with spinal cord injuries will have decreased erections related to the extent of the injury. Patients who have undergone pelvic surgery such as radical prostatectomy, cystectomy or colectomy may have injury to the cavernous nerves that control erection. Long-standing diabetes may affect some nerves as well as causing impotence.

Hormonal Causes of Impotence

Diseases and conditions that decrease circulating testosterone in the body, such as castration or hormonal therapy used to treat prostate cancer, will decrease libido and impair erections.

Vascular Causes of Impotence

Diseases such as high blood pressure, high triglyceride and cholesterol levels in the blood, cigarette smoking and diabetes mellitus, and treatments such as pelvic irradiation to treat prostate, bladder and rectal cancers, may damage blood vessels to the penis over time. There is strong epidemiological association between heart disease, hypertension, low levels of high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and impotence. Patients with Peyronnie’s disease which causes curvature of the penis, trauma, diabetes or old age may have damage to the spongy tissue of the penis, causing the veins to be more “leaky,” which can lead to impotence.

Drugs and Impotence

Certain anti-depressants or anti-psychotics have been associated with impotence, especially those drugs that regulate serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine. These include Prozac, Zoloft and Paxil. Beta-blockers and thiazide agents used to treat hypertension are associated with impotence. Cimetidine, a drug to treat acid reflux disease; chronic alcoholism; estrogens and drugs with anti-androgen action such as ketoconazole, and spironolactone can cause impotence, decreased libido and male breast enlargement. Even moderate alcohol intake may have an effect.

Aging and diseases which cause impotence

Aging, even in healthy men causes a progressive decline in sexual function. Medical studies have discovered that as men age, there is a decrease in turgidity, or “stiffness,” of erections as well as a decrease in the force and volume of ejaculation. Also, with normal aging, there is an increase in the length of time required between erections after orgasm, called the refractory period. Further, the sensitivity to touch decreases over time as do serum testosterone levels, with an associated decrease in desire. Studies indicate that half of all men with diabetes will eventually develop impotence. In addition, those with liver cirrhosis, chronic renal failure or coronary artery disease have a high incidence of impotence.

Normal male sexual function is a constellation of processes: sexual desire or libido, the erection when the penis becomes firm, release of semen (ejaculation) and orgasm. Erectile dysfunction — commonly known as impotence — is defined as the inability to achieve or maintain an erection that is sufficient for satisfactory sexual activity. However, almost all men who have impotence can overcome it.

– Sexual desire, the release and expulsion of semen — emission and ejaculation — and the ability to have an orgasm occur via separate, distinct physical mechanisms. Due to a variety of reasons they can be dissociated from one another. For example, orgasm and ejaculation can occur without erection.

– Sexual desire or libido is determined mainly by the amount of testosterone in the body. As men get older the amount of testosterone that circulates slowly declines, decreasing libido. A decrease in libido also may result from depression and various medical problems that affect overall mental and physical well being.

– Ejaculation, the expulsion of semen during sexual activity, is affected by testosterone levels and medications as well as by the normal anatomy of the prostate and bladder. Decreasing amounts of testosterone, often occurring as a result of normal aging, will affect the volume of the ejaculate. Certain medications may also affect ejaculation. With aging, the volume of the ejaculate decreases.

– Surgery on the prostate or bladder and radiation can affect the amount of secretion produced as well as the ability to have normal ejaculation.

– Orgasm occurs as an experience of intense physical and emotional pleasure during the sexual act, and can occur separately and independently from erections, emission or ejaculation. Many factors, including emotional and psychological considerations, contribute to the experience of orgasm.

It is important to realize that male sexual function is defined by more than just the ability to have an erection. Mutually satisfactory sexual relationships can be maintained in the presence of impotence.

Chronic disease includes other cancer, hypertension, cardiac disease, diabetes or stroke.

Risk factors include antidepressant use, consumption of more than two alcoholic drinks per day, smoking, obesity, lack of exercise and watching television for more than 8.5 hours per week.

Impotence and Cancer Surgery or Radiation

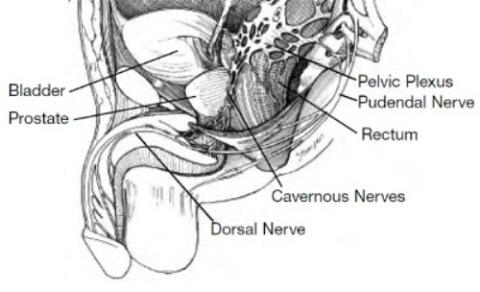

Impotence following major pelvic surgery or radiation, including prostate and bladder surgery, has been widely reported. During a radical prostatectomy the nerves which allow erection, called cavernous nerve bundles, and which lie within millimeters behind and on the side of the prostatic capsule, may be injured by being cut or separated from the prostate. This may cause temporary or permanent impotence, although sexual desire and the ability to achieve orgasm should remain. As discussed in Chapter Five: Other Causes of Impotence, radiation to the prostate, the bladder or rectum can damage the cavernous nerves as well.

The “nerve-sparing” radical prostatectomy or radical cysto-prostatectomy procedures to remove a cancerous prostate or bladder attempts to preserve these cavernous nerve bundles without compromising complete cancer removal. In the hands of an experienced surgeon, if both nerve bundles are spared, 50 to 90 percent of patients — depending on age and health — may have an eventual return of unassisted erectile function over time. When only one nerve bundle is spared, the percentage of patients that have return of erections over time is 25 to 50 percent. If a non-nerve sparing technique is used, the potency rate drops to 16 percent or less, depending on patient age.

Aside from the degree of nerve-sparing surgery performed, other factors are associated with impotence after radical prostatectomy.

- The biggest risk factor is age. Studies have shown that while the majority of men under 50 years of age are potent after radical prostatectomy, only 22 percent of men over the age of 70 are potent after the procedure.

- Other medical conditions that increase the risk of impotence include hypertension, smoking, diabetes, elevated cholesterol (hyperlipidemia) and heart disease. Depression, as well as other psychogenic factors, may affect psychological well being and recovery of potency.

- Unfavorable clinical and pathological stage of cancer also is associated with worse potency outcomes, as these men may not be candidates for a nerve-sparing approach because it may leave cancer behind.

It should be remembered that even if both nerve bundles are spared, with their proximity to the prostate (See Figure), these structures will likely suffer some injury that will take time to heal. Healing of the cavernous nerves and return of any unassisted sexual function may not begin until six months or more after surgery; however, it usually continues to improve over the next two to three years. Indeed a large percentage of men may not recover sufficient function for 18 to 24 months, some even longer. With prolonged disuse, the smooth muscles of the penis may atrophy, which worsens erections. Early and aggressive treatment of impotence with oral or injection medication may improve and speed up recovery of erectile function.

For men undergoing radiation, the amount and extent of radiation as well as whether or not they are treated with hormone therapy correlates with the likelihood of impotence, either temporary or permanent. The reduction in libido and possible difficulties with erections from the use of hormone therapy is generally reversible when the therapy is discontinued. The likelihood of irreversible effects is related to patient age, pre-treatment sexual function and the length of time hormone therapy is given.

Even if impotence is present after surgery or radiation alone, the ability to achieve an orgasm should remain. However, with the prostate removed there is no ejaculate although some secretions may remain. During orgasm, there is no emission or expulsion of semen. The ejaculate volume will decrease with radiation as well.